Introduction

1. Reveal the ultimate dimension of cellular heterogeneity: from cell populations to single cells, and from fragments to full lengths.

Traditional single-cell sequencing (such as 10x Genomics 3’ or 5’ end sequencing) can only capture the terminal fragments of transcripts, and has the following limitations:

① Blind spots for isoforms: It is unable to distinguish different splicing variants of the same gene (such as alternative promoters, exon skipping), and these isoforms may have opposite functions (such as oncogenic and tumor-suppressive types).

② Missing complex structural variations: It is difficult to accurately assemble the full-length structures of fusion genes.

The breakthroughs of single-cell third-generation full-length transcriptome sequencing lie in:

✔ Full-length coverage: It can directly read the complete sequence of transcripts from the 5’ cap to the 3’ tail, precisely analyzing splicing sites, UTR variations and RNA editing events.

✔ Single-molecule resolution: It can independently analyze the transcriptome of each cell, avoiding the masking of rare cell types (such as cancer stem cells or immune response cells) due to population averaging.

2. Analyze the dynamic network of transcriptional regulation: from sequence to function.

Full-length transcriptome data provides multi-level information for understanding the regulation of gene expression:

① Diversity of promoters and terminators: The use of different promoters by the same gene can produce proteins with very different functions (such as the pro-apoptotic or pro-survival functions of p53 isoforms).

② Regulatory mechanisms of alternative splicing: By analyzing the activity of splicing factors at the single-cell level, the molecular switches for cell state transitions can be revealed (such as the dynamic changes of Wnt pathway isoforms during embryonic development).

3. A revolutionary tool for precision medicine and research on disease mechanisms.

In clinical and translational research, single-cell third-generation full-length transcriptome sequencing is becoming an irreplaceable technology:

① Analysis of cancer heterogeneity: Identify specific splicing variants that promote metastasis in the tumor microenvironment (such as CD44v6 promoting EMT) and new fusion gene subtypes related to drug resistance (such as BCR-ABL1).

② Diagnosis of rare diseases: Directly detect recessive pathogenic variations caused by splicing errors in single cells (such as exon skipping of SMN1/2 in spinal muscular atrophy).

③ Optimization of immunotherapy: Analyze the full-length diversity of T cell receptors (TCR) to predict the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

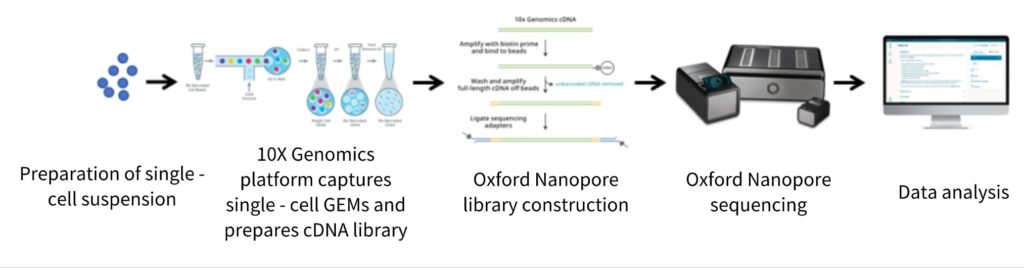

principle

Single-cell third-generation full-length transcriptome sequencing technology is constructed based on the 10x Genomics single-cell capture platform and the Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing technology. It can not only analyze the panorama of gene expression in individual cells but also accurately capture the complete structural information of mRNA. By integrating the advantages of single-cell technology and third-generation long-read sequencing, this technology advances single-cell transcriptome analysis from the level of gene expression to that of transcript isoforms.

advantages

✔ Comprehensive transcript isoform analysis: Accurately analyze all isoform types and provide complete information presentation.

✔ Panoramic analysis of fusion genes: Decode fusion genes in an all-round way and reveal their overall characteristics.

✔ Refined classification of cell subpopulations: Obtain more precise cell subpopulations and improve the accuracy of research results.

✔ Real-time monitoring of alternative splicing: Track change dynamics in real time and control the evolution process.

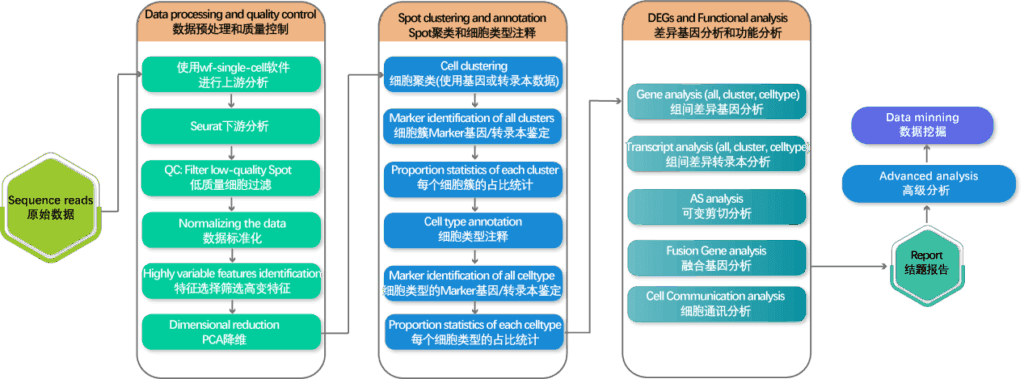

Data analysis process

Presentation of test results

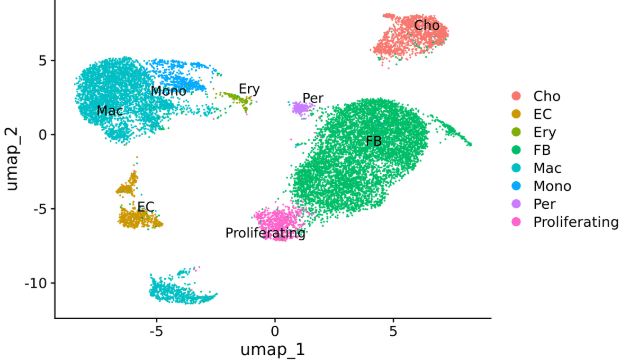

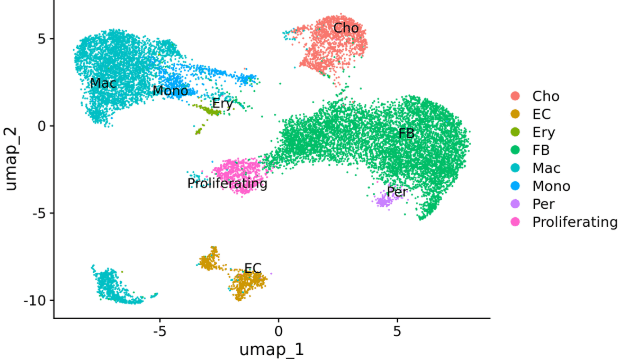

Sample: Mouse lung tissue

Single-cell platform: 10X 3ʹ v3

Third-generation platform: Oxford Nanopore

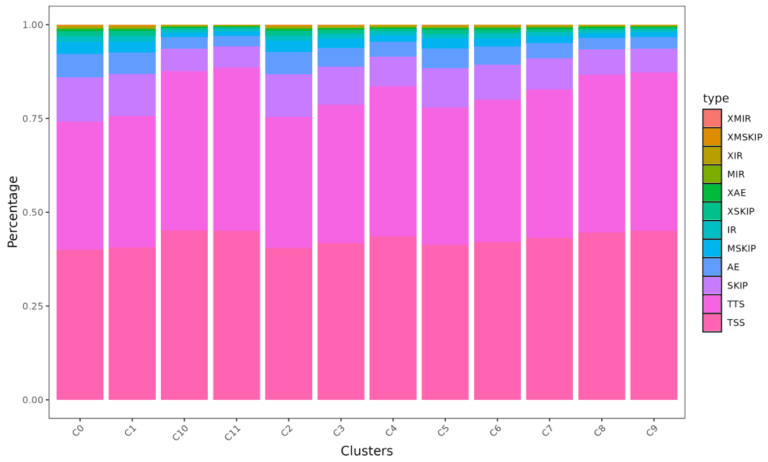

1. Cell type clustering

2. Alternative splicing analysis

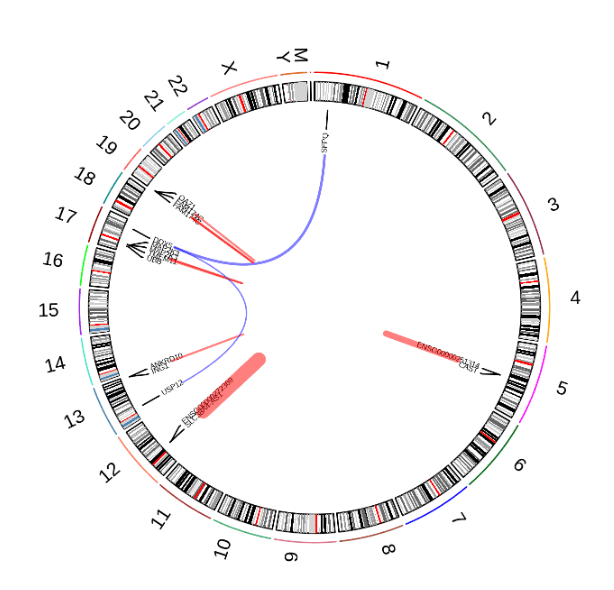

3. Fusion gene analysis

Literature cases

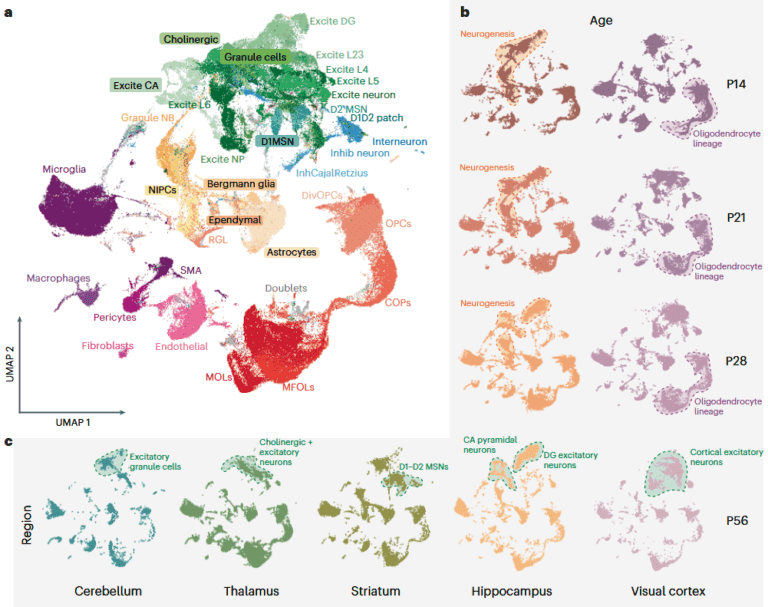

1. Research on the hippocampus and visual cortex of the brain.

Title:Single-cell long-read sequencing-based mapping reveals specialized splicing patterns in developing and adult mouse and human brain

Journal:Nature Neuroscience

IF:20

Sample information:

Mouse samples covering different developmental stages (P14, P21, P28, and P56) and multiple brain regions (hippocampus, visual cortex, striatum, thalamus, cerebellum) were included. Meanwhile, 6 healthy human brain samples (including the hippocampus, with 3 males and 3 females) were also obtained.

Research findings:

- Widespread existence of splicing diversity

- 72% of genes showed differences in full-length isoform expression in at least one dimension (cell subtype, brain region, developmental stage). Among them, the isoform variability of neurons was higher than that of glial cells and progenitor cells, indicating that the regulation in neurons is more complex.

- Cell type-specific splicing patterns were significant. For example, the isoform variability of excitatory neurons was mainly reflected among subtypes, while that of inhibitory neurons was more obvious in differences between ages and brain regions.

2. Splicing characteristics in regions and developmental stages

- Brain region specificity: Astrocytes in the thalamus and cerebellum showed strong differences in transcriptional start site (TSS), polyadenylation (poly (A)) site, and exon regulation, suggesting the important impact of splicing on the morphology and function of brain regions.

- Developmental regulation: Adolescence (P21 – P28) is a critical transition period for splicing variability. At this time, the standard deviation of exon inclusion variability among cell types is the highest, and the splicing patterns of synapse-related genes change significantly.

3. Splicing conservation and specificity between species

- The cell type-specific splicing in mice is mostly conserved in the human hippocampus (such as the extremely variable exons in groups E3 and E5), but the human brain has additional cell type-specific splicing, which may represent functionally acquired isoforms during evolution.

4. Association between splicing and function as well as disease

- Extremely variable exons (EVExs) affect protein domains (such as fibronectin type III domain), participate in cell recognition and signal transduction, and are closely related to neuronal functions.

- 20% of EVExs are regulated by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), and 16% of EVExs are related to known splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTLs), and most of them are involved in neurological diseases (such as Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia).

5. Splicing characteristics of glial cells

- The splicing patterns of the oligodendrocyte lineage change significantly during the differentiation process, which is inconsistent with the gene expression patterns, suggesting that splicing has an independent role in the establishment of cell identity.

Core conclusion:

Splicing diversity is widely present in cell subtypes, brain regions, and developmental stages. It is a key mechanism for shaping the specialization of brain functions and cell identity, and some patterns are conserved between humans and mice. These findings provide a new perspective for understanding the molecular mechanisms of brain development, function, and neurological diseases.